Those OTHER Fortified Wines - Madeira and Vin Doux Naturels

In which I become deeply intrigued by a category of wines immediately after being examined on them, i.e. too late.

My exposure to Madeira was extremely limited before I took the WSET course on fortified wines. I had used a bit for cooking. I knew it came from and was named for an island that belongs to Portugal but is closer to Morocco, because colonialism. I could tell customers in my previous job that Sercial was dry and Malmsey was sweet. Tucked in the trove of obscure and useless facts that takes up a good share of my brain was the knowledge that George Washington reportedly drank an entire bottle of Madeira every day.

My level 3 exam included a question on Vin Doux Naturels, specifically Muscat de Beaumes de Venise, which I had seen exactly once in the wild and never tried. Fortunately it was a theory question about production, which I had studied in great detail about twelve hours before the exam. I had given zero thought to the existence of other Vin Doux Naturels.

Then there’s Rutherglen Muscat, another wine about which I’ve happily aced a question about production despite never having actually tried the wine. Today I will not be going into Rutherglen, because to this day I have tasted only one, and I don’t feel like I have anywhere near the handle on it necessary to tell anyone else about it.

But the first two. It’s not as though I have extensive experience with them at this point, but even a few encounters have been a revelation. The sad thing is that while I was taking the class, I was so absorbed in getting through the material and internalizing the facts for the exam that I forgot to slow down and enjoy the wine itself - and there is a lot to enjoy in these lesser-known fortified wines.

In fact, it was at the very end of my exam while second, third, and fourth-guessing my blind tasting that not only did the wine snap into clarity as a Sercial Madeira, but I also realized that I really, really liked it. That seemed pretty irrelevant while studying, but the truth is that our personal experience of the wine is incredibly significant in getting us into this field in the first place, and if there is a lesson to be taken from this, it is that I don’t ever want to let myself get so mired in the minutiae of it all that I forget the joy of wine.

Madeira

So let me tell you about my new friend, Madeira. Madeira isn’t just a wine, it’s also the island where that wine is made, and the Portuguese word for “wood;” settlers seem to have named the island for its ample supply of trees. The island was uninhabited before it was settled around 1420, but there is archaeological evidence that Vikings visited sometime in the 900s. Like other fortified wines, Madeira finds its origins in the challenges of shipping wine in barrels over long distances. Adding some brandy to the wine to raise the alcohol content kept the wine from spoiling, and people came to enjoy the higher alcohol styles. During shipping, Madeira wine barrels were sometimes carried on the ship’s deck to act as ballast, so in addition to the oxidation typical of wines fermented or matured in barrels, they were subjected to heat, rain, and other weather conditions. The sunlight and heat maderized - essentially cooked - the wine, creating flavors of nuts, caramel, cooked fruit, and burnt sugar, which people also grew to enjoy as an integral part of the wine.

.Today Madeiras are fortified with a 95-96% ABV neutral-flavored grape-based spirit, and aged in heated conditions to reproduce the effects of sun on a ship’s deck. The best quality Madeiras are aged in large barrels in warm warehouses for long periods of time. Some people prefer a style of Madeira called Rainwater, with lighter body and lower alcohol that tries to reproduce the slightly rain-diluted barrels of the past.

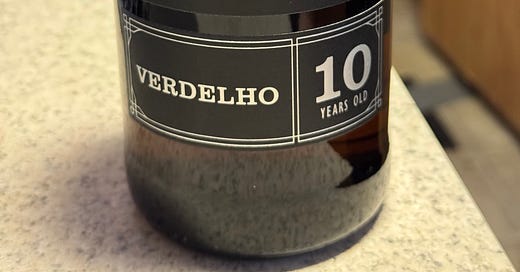

Most Madeira is made from Tinta Negra, a high yield and easy to grow red grape that is used in less expensive wines labeled by their level of sweetness. Better quality Madeira is made from the five noble grape varieties: Sercial (dry and off-dry), Verdelho (medium dry), Boal (medium sweet), Malvasia (sweet), and Terrantez (extremely rare and used for medium-dry and medium-sweet styles). Side note, “Malvasia” isn’t really a grape variety, but rather an umbrella term for a bunch of unrelated varieties; on Madeira they use Malvasia Candida and Malvasia de Sao Jorge. File that away for an eventual post titled “Ways Wine Gives Me a Headache That Have Nothing To Do With a Hangover.”

Drink your Madeira with strong cheese regardless of sweetness. Dry Madeiras work well with mushroom dishes, shellfish, and almonds, while sweet styles pair better with chocolate, caramel, or almond desserts. Foie gras is also a classic pairing.

Vin Doux Naturels, or VDN

These are the sweet, fortified wines of southern France, made in the Rhône Valley, Languedoc, and Roussillon. The whites, like Muscat de Beaumes de Venise, are made from Muscat au Petit Grains or Muscat of Alexandria (because of course, like Malvasia, Muscat is actually a bunch of different kinds of grapes, some related and some not). Reds are made mostly from Grenache Noir, which is just what most of us know as Grenache or Garnacha but differentiated from the Blanc and Gris versions - genetic mutations that are also allowed in blends in Roussillon in varying amounts. You will find these wines labeled by their Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC), a geographically designated area with specific rules about grapes that can be used, growing and production methods, etc.

Muscat de Beaumes de Venise and Vin Doux Naturel Rasteau are AOCs in the Rhône. In the Languedoc are Muscat de Frontignan and Muscat de St. Jean de Minervois. From Roussillon, which produces the most VDN, the AOCs are Grand Roussillon, Banyuls (mostly red), Banyuls Grand Cru (solely red, requiring 75% Grenache Noir), Maury (mostly red, 75% Grenache Noir), Muscat de Rivesaltes (a blend of Muscats, unaged), and Rivesaltes (made in a range of styles). Some of these can also be labeled as Hors d’Age, which is aged oxidatively in barrels for several years, or Rancio, which is a somewhat mysterious term for aromas and flavors of leather, varnish, and coffee that come from some combination of barrels, oxidation, temperature, and time.

Unaged fortified Muscats are usually light, fruity, and floral, and go best with desserts that are equally light and feature tropical fruits, apples, pears, or peaches. Unaged fortified Grenache tastes, well, almost alarming like any other Grenache - a handful of juicy red fruit - but extra sweet and boozy. I have had mine as dessert rather than with dessert, but it would be a good accompaniment to berry desserts or milk chocolate. The aged versions go well with richer desserts like creme brûlée, dark chocolate, caramel, and toffee, but they’re so complex that you might want to just sip them sans food, as I am with this Rivesaltes Rancio, which more than stands up on its own. And I can verify from recent personal experience that a Banyuls Hors d’Age is excellent with Trader Joe’s Ultra Chocolate ice cream.

Aside from their usual place as dessert wines, as we shift toward cooler weather, fortified wines are fantastic for cozy nights at home, around a fire if you have one, wrapped in a blanket if you don’t. I do advise moderation! The hangover from sweet, high alcohol wines is no joke. Fortunately, the high ABV means these wines can also last longer after they’ve been opened - usually 4-6 weeks if refrigerated - so you can confidently take your time finishing them.

Here’s to trying new things! Cheers, all.

My new year’s cruise stops in Madeira for a day and I’m hoping for the chance to do some wine tasting there. :-) I shall bookmark this so I don’t sound stupid when I get there. 🤣🍷

Thought you especially would appreciate this, Stacey. Keep keeping us informed! Your knowledge about wine is a treasure.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/26/opinion/wine-sober-october.html?unlocked_article_code=1.VE4.iQGu.8Zvsqy2W6Fy6&smid=url-share