Regenerative Viticulture

In which I stop nattering on about writing my paper and actually tell you about it

Let’s start with what is usually called “conventional agriculture,” or the industrial style of agriculture that has been at the center of our food system since World War II. The goal of conventional agriculture is to create profit. In order to do this, you grow as much of your agricultural product as possible, as uniformly as possible, for as little money as possible. This means minimizing labor costs and complications that may require hands-on solutions or risk that loss of crops. Within conventional agriculture, soil is merely a medium for growing, and the effect of farming methods on the soil itself is simply not a factor. The ecosystem as a whole is similarly not a factor. Common techniques in conventional agriculture include growing a single-crop monoculture, plowing and tilling, machine picking, and using synthetic pesticides, herbicides, fungicides, and fertilizers.

Why this isn’t great, in case it isn’t painfully obvious: Monocultures take nutrients from the soil but don’t cycle them back in; this is why fields need fallow periods every so often, but even a rest period doesn’t fully restore soil’s fertility. Running tractors through a field compacts the soil, making it less water absorbent and reducing the ability of worms and microorganisms to live within it. Plowing and tilling disturbs the life under the soil, and releases carbon into the atmosphere. Machines create carbon dioxide emissions. Chemicals kill off other life forms and drain into water supplies. Over time, we reduce the soil’s ability to support plant life and damage our own ability to produce food, while the food we do have is filled with harmful chemicals.

Also, we’re experiencing a climate crisis that has a whole lot to do with too much carbon in the atmosphere, and not enough in the soil. Conventional agriculture releases more carbon into the atmosphere, while interfering with the soil’s ability to absorb carbon.

I don’t know about you, but when people talk about climate change, I often feel powerless and hopeless. The problem seems insurmountable, and the tiny changes I can make seem about as effective as trying to raise the water level of the ocean by throwing handfuls of sand. For a very long time, everything I saw about “combatting climate change” was simply some way to marginally slow the inevitable consequence of damage already done.

But then I learned about a way of farming that actually reverses damage to the soil, water, and air, and that has the potential to absorb and properly direct excess carbon: regenerative agriculture. You can get a good overview from a non-boring source by hitting Netflix and watching “Kiss the Ground.”

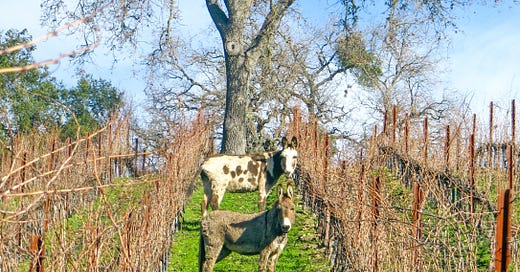

Well, guess what? You can grow grapes regeneratively, too! If you’ve been around vineyards, you might assume they’re supposed to look like this:

Trellised grapevines spaced widely to allow for tractors. Bare ground between and around the vines. Aside from a distant tree, no non-grape plants to be seen.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

A vineyard can have ground cover plants. It can be grazed by sheep, pigs, or donkeys. Vines can coexist with trees. Wildlife can make their homes above and below the soil. All of it can be grown without mowing or tilling or spraying chemicals all over the place - and the vines can be healthier and more resilient and produce better fruit than conventionally farmed vines.

Farmed regeneratively, the vineyard can actually restore nutrients to the soil, encourage microbiomes, enhance biodiversity, absorb carbon, and use water more efficiently. They can also do cool things like creating and using biochar. What the heck is biochar, you ask? It’s a form of charcoal that is made when you partially burn organic waste in a limited oxygen environment. You can then burn it as a cleaner energy source, or put it into the soil, where it holds carbon and enhances soil fertility.

I’ve been drawn to the regenerative viticulture movement as a way to produce wine that doesn’t just do less bad stuff, but rather tries to proactively correct the damage of the past. Of course, none of this is easy, and it requires some specialized techniques to handle a vineyard when you can’t just spray the bugs (or mold, or viruses, or weeds) away. And, of course, its impact depends greatly on how many vineyards are doing it.

Regenerative farming isn’t necessarily new, but I guess you could say it’s fairly new to the public consciousness, especially in the world of wine, so there are still a lot of questions about implementation, standards, certifications, how to communicate to consumers that wine has been made regeneratively, etc. A couple of bodies that certify vineyards and wine producers are the Regenerative Organic Alliance and and the Regenerative Viticulture Alliance, and you can look at their websites for lists of producers who are farming regeneratively. Some of my favorite regenerative certified producers are Gundlach Bundschu, Tablas Creek, Grgich Hills, Raventós i Blanc, and Familia Torres.

How does this compare to organic and biodynamic farming? There is some overlap with both, and sometimes organic and biodynamic growers are farming regeneratively. But in the strictest definitions, regenerative viticulture goes beyond organic in that it is more than just a limitation on what you can’t put on the plants; it also implements positive actions like ground cover and integrating animals. While many of the vineyard practices are the same, regenerative viticulture doesn’t share the philosophical/cosmological aspect of biodynamics. No moon cycles or cow horns here, just a very pragmatic approach to the overall health of the soil and ecosystem.

The slogan of the Regenerative Organic Alliance is “Farm like the world depends on it,” and that’s what regenerative viticulture is all about: tending vineyards for the future viability of the planet. Why isn’t everyone farming this way? Good question.

I may not be able to answer that question, but I’m happy to answer others you may have about regenerative viticulture. Leave them in the comments or email them to me at stacey@justasmidge.me.

For paid subscribers, the link to my full research paper is below the paywall. Through August 12, all new paid subscribers will be supporting the next course in my WSET Diploma, and with my thanks you will receive 10% off monthly or annual subscriptions. That’s only $4.50/month or $45/year. Cheers!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Just a Smidge to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.